“Mastery, Tyranny and Desire: Thomas Thistlewood and his slaves in the Anglo-Jamaican World,” by Trevor Burnard

Even with a shared legacy of slavery and a realization that it remains the crucial shaper of not just the African Diaspora but the political, economic and social foundation of the Caribbean, “Mastery Tyranny and Desire” still comes across as a revelatory, appalling shock. I was tempted to think that the black person’s awareness of slavery was much like the Jew’s knowledge of the holocaust. That even if one had not experienced it directly, the event was such a traumatic shaper of subsequent Jewish life that one absorbed all its facets as common knowledge. But in both cases I was wrong. There are still facets to the holocaust, still being uncovered and there are still aspects of slavery (the black holocaust) still being discovered anew.

In that sense, this book, an analysis of slave and property owner, Thomas Thistlewood’s diaries becomes essential. From 1750 when he sailed to Jamaica, to 1786 when he died at sixty-five, Thomas Thistlewood, middle class before his time, wrote in his diary every day. Most of it was preserved and are kept in museums worldwide, but put together they stand as a valuable, shocking and essential document, in many ways the most essential of all the slavery accounts from whites. Oddly enough it is the limitations that give the diaries their power.

Thistlewood was by nobody’s standards a remarkable man. He was a man of means who made wealth for himself in the new world by being an overseer; a man who eventually bought his own property that included a humble two storey house and several slaves. He was no great wit like Jefferson, nor did he sprinkle his words with moral contempt like historian Edward Long, nor was he gifted with self-analysis like many of his peers. But he did keep a diary for most of his life, which was in itself remarkable for a man.

Trevor Burnard, even when he is analyzing Thistlewood’s words and reminding the reader of the context, is wise enough to know when to get out of the way and let Thistlewood speak for himself. Thistlewood’s words are both artless and heartless. He would list his several sexual dalliances as if they were shopping lists; most times in abbreviations mixed with schoolboy Latin as if he feared discovery. Given that a large portion of his sexual conquests were married white women that was understandable. A typical episode would be written like this:

“Cum E.T.—cum illa in nocte quinque tempora. Sed non bene”

Translated: “Had sex with Lady Elizabeth Toyne (wife of his employer) last night. Not very good.”

The diaries are also bracing in their depiction of violence. Whatever perspective one uses while reading this book, whether the reader transports himself to the time or judges the time with a distance, the details are still horrendous precisely because they are so matter-of-fact. Perhaps what is most striking about that time, is how behaviour that would today be defined as sociopathic was given free reign:

“His sexual appetite appears less that of a Caribbean Casanova than the unnatural and bestial longings of a quintessential sexual predator and rapist. His willingness to subject his slaves to horrific punishments, which include savage whippings of up to 350 lashes and sadistic tortures of his own invention such as Derby’s dose, in which a slave defecated in the mouth of another slave’s mouth and was then wired shut, reveal Thistlewood as a brutal sociopath.”P31

One could explain Thistlewood’s actions as mere symptoms of his time and one would be right, but not as Burnard deftly explains, in the way one might think. The fact is, Jamaica, unlike the United states and the Latin American colonies was never properly settled. There were no magnificent buildings or strong social structures to force the rule of either law or “civilized” behaviour. That left many men to make their own laws without worrying about any moral authority beyond their own conscience. It also allowed for men to explore the darker sides of their sexual nature unencumbered by any fear of retribution. It asks the reader a pointed question. If you could get away with it as they could, would you do it? There’s a theory that Jack the Ripper escaped to the Caribbean, and if he did, he could not have picked a better place.

The Thistlewood diaries provide much rich information for the historical writer but even more for the writer interested in deciphering the European mind and its inherent contradictions and hypocrisies. I took both from this book, the shopping list of atrocities as well as the oxymoron of enlightened Europeans subjecting other people to slavery. The book forces readers to not only witness the thinking of the slave owner but to empathise with it. Here the diaries succeed in a way the very best fiction hopes to.

But the book also exposes the limitations of fiction and the line that every writer must draw for himself when dealing with facts. What does one do when fact is more shocking than fiction? What does one do when the absolute brutality of truth would stretch the boundaries of plausibility in fiction? It is hard for people today, in particular white people to believe that any civilized race could have been capable of such stunning brutality. It’s part of the collective denial that allowed for concentration camps half a century ago and ethnic cleansing today.

But it poses the great challenge; how much is too much? How does one deal with the hand grenade of slavery, a polarizing topic, even today? The first few pages of my novel raised consternation from some initial readers who simply refused to believe that an entire nation of people could be so complicit in atrocity with not one person realizing that this was wrong. How do I as a writer make that plausible? Do I serve history wrong by including a white character appalled by slavery? That type of European would not emerge until 35 years after my novel begins.

Perhaps what I took from this book, even more than the vital and vivid historical detail is the reminder (or is it warning?) that the duty of the novelist is not the same of the historian, or polemicist or philosopher. That I am at the service of the story and not the political position, or my desire for literary revenge.

I have to take myself to the point that Spielberg reached in Schindler’s list where he had to accept that even the villain deserves complexity and humanity even as he does the shockingly inhumane. Two friends asked why I am writing this book and my response then was that, it was my duty to not let “those motherf*****s ever forget what they did to us.” There is still a part of me that believes that, but I had to make it subordinate to my duty as a novelist. I have to remember every time I sit down to write that the blackest of evils is still pretty gray and that a simplistic depiction of cruelty serves nobody, not even the victims of it. This is a hard lesson for a novelist still furious at history and I would be a liar if I said that I have fully accepted it.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

CHEEVER, A LIFE, by Blake Bailey: Engrossing, maddening, funny but also unbearably sad, Cheever's greatest work of fiction may have been himself

In Hazard, by Richard Hughes

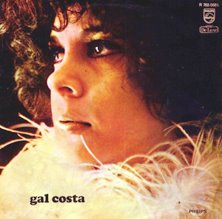

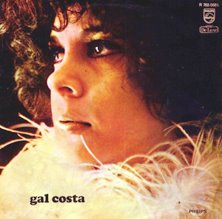

-image007.jpg)

GAL COSTA. You get the feeling that the tropicalia subversives were really trying to make a hit with this one, and it's all the better for it. Beck would have to become a scientologist to make this...er...wait a minute....

As Of The Writing I, Marlon James

- Marlon James

- Minneapolis/ St. Paul, United States

John Crow's Devil Paperback UK

John Crow's Devil Paperback USA

READING RIGHT NOW...

CHEEVER, A LIFE, by Blake Bailey: Engrossing, maddening, funny but also unbearably sad, Cheever's greatest work of fiction may have been himself

Reading Right Now...

In Hazard, by Richard Hughes

Books Of the Moment

- American Rust, by Phillip Meyer

- The Liar's Club, by Mary Karr

- The Forever War, by Dexter Filkins

- Sacred Violence, by Paul W. Kahn

- The Pilgrim Hawk, by Glenway Wescott

Rocking My World

-image007.jpg)

GAL COSTA. You get the feeling that the tropicalia subversives were really trying to make a hit with this one, and it's all the better for it. Beck would have to become a scientologist to make this...er...wait a minute....

Other Sonic Obsessions - Hiphop Bebop Don't Stop

- Beastie Boys - Paul's Boutique

- A tribe Called Qwest - The Low End Theory

- A Tribe Called Quest - Peoples Instinctive Travels...

- KMD - Black Bastards

- De La Soul Is Dead

- Mad Villian - Mad Villainy

- Stereo MC's - DJ Kicks

- Miles Davis - Sorcerer

- John Coltrane - Live In Paris