The great Jamaican novelist Anthony Winkler, no stranger to strangeness, chose 1975 to leave the US for Jamaica, a return to teach at a country school. At the time this flew in the face of conventional wisdom and even basic good sense—the rest of Jamaica was too busy trying to leave— and he must have noticed how empty the arrivals section was compared to the chaos in departures. But he did get a good book out of it. So who knows, maybe I’ll get a good book out my colonization in reverse. It’s September 10, 2007 and I have been in St. Paul, Minnesota for nearly a month now. While I fully understand Winkler’s reasons for going back, it’s worth noting that he did not stay. If you are a writer in Jamaica, maybe even in the Caribbean there comes a point when you just have to go.

I remember last year talking to a friend of mine, an artist. His work had once blazed with a fierce inventiveness, the kind of brief flashes of brilliance that Jamaicans can give you sometimes that makes you hope, wish that it would lead to something not just revolutionary but consistently groundbreaking. But like many before him, his brilliance was just a flash, and while he is still good, his work reflects a curious stasis, an unconscious failure of nerve, and a lack of hunger that has infected everything he has done. In Jamaica it is simply too easy to make good by not being good enough. I told him that he simply had to leave. It was time. His talent or more importantly his search had come to the point where Jamaica could no longer provide answers or even good questions. His choice was to either stay and contract (though make money doing it) or leave for somewhere, anywhere that would explode his point of view and challenge his thinking on what was good, normal, or even right. He needed a new space; somewhere he was not entitled to and had everything to prove. His art depended on it.

I know because that was my case as well. I find it hard explaining to people that I had grown tired of graphic design by 2000. By late 2000 I knew I had outgrown my life but could not think of what would come next, whether mediocrity or death. So I chose both. Or rather I decided to make mediocrity kill me. Nobody understood that the supposedly great design that I was doing took few minutes to create, few hours to execute and nothing to accomplish. I was doing substandard work and knew it. I also knew that nobody else in Jamaica knew I was doing it. I was not interested in getting better nor did I need to. It took me five more years to realize how wrong this was.

Years ago I asked a friend in UWI’s English Department what would it take to lecture on campus. Over the phone she said one of two things needed to happen: either one of [them] died or I became too big a writer to ignore. I’m not scared of burning bridges but that’s not why I left. Writing was the first activity I ever did that scared the daylights out of me. Many Jamaicans —and this is no disrespect to them— thought my work was good, but I did not quite believe it. I knew how easy it was to be lauded for merely doing something as opposed to doing it well. What’s more I was stuck here, while my friend Kwesi left to make films. This was a friend I looked up to because he was worldly and intelligent, had the most books I’ve ever seen, took what I said seriously and had high standards for himself. But when he left I knew why. Had he stayed he would have become a lot like some of the people he left behind. Sure he might have been able to buy a range rover but he would have lost his soul and by that I’m not trying to be dippy or metaphysical: By soul I mean the inner motivation to do something purely for the sake of doing it rather than for something external. Like good money.

That probably isn’t very clear. Let me put it this way. George Clinton once said funk is its own reward, meaning the greatest return, the deepest thrill in what he did was in the very act of doing it. I think and he’ll probably say I’m dead wrong (but it’s my impression and my blog), that Kwesi needed to be doing something where the very act of doing it was it’s own reward. I think that’s why he left and I know that’s why I had to.

So I finally left in August, even though just about everybody would tell you that I left from 2005. Just because some place is your home doesn’t mean you can live there. Jamaica became a base, a place to fly out from. I was in New York so much that customs started to suspect me of living there illegally. There was nothing more depressing than coming back to Jamaica and to be immediately thrust back into a life of trying to make money doing something I had no wish to. I did not start writing to find a new way to make money (boy would that have been a mistake —even though I’m not doing bad, thanks for asking) but I did get a degree in creative writing so that I could teach. And earn some money. I love my country but I’ve never missed it, perhaps because I have never forgotten the reasons I left.

When I told Kwesi what I was about to do, I simply recited the bottom line that I was in it for steady income. I think it disappointed him in some way, that way in which your friends sound polite and supportive but really think you can do better. What I wanted to say and should have said is that I love teaching and think I was kinda born to do it. I don’t know if that makes me a teacher, but I have to tell you, two days ago when a student came up to me and said he wasn’t supposed to be in my class, but liked it so much that he was going to drop his other class to take mine, well, that felt like something a better writer than me could have described. It’s not because I love the idea of “shaping young minds,” quite frankly I think that’s bullshit. I think I love it because like what Clinton said about funk, teaching is its own reward. I’m a writer first, but this is not a stopgap until Oprah returns my calls. If I leave this world with some people thinking I was a good teacher that wrote some books, that’s fine too.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

CHEEVER, A LIFE, by Blake Bailey: Engrossing, maddening, funny but also unbearably sad, Cheever's greatest work of fiction may have been himself

In Hazard, by Richard Hughes

-image007.jpg)

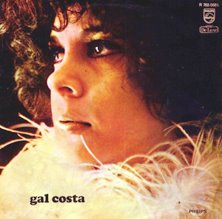

GAL COSTA. You get the feeling that the tropicalia subversives were really trying to make a hit with this one, and it's all the better for it. Beck would have to become a scientologist to make this...er...wait a minute....

As Of The Writing I, Marlon James

- Marlon James

- Minneapolis/ St. Paul, United States

John Crow's Devil Paperback UK

John Crow's Devil Paperback USA

READING RIGHT NOW...

CHEEVER, A LIFE, by Blake Bailey: Engrossing, maddening, funny but also unbearably sad, Cheever's greatest work of fiction may have been himself

Reading Right Now...

In Hazard, by Richard Hughes

Books Of the Moment

- American Rust, by Phillip Meyer

- The Liar's Club, by Mary Karr

- The Forever War, by Dexter Filkins

- Sacred Violence, by Paul W. Kahn

- The Pilgrim Hawk, by Glenway Wescott

Rocking My World

-image007.jpg)

GAL COSTA. You get the feeling that the tropicalia subversives were really trying to make a hit with this one, and it's all the better for it. Beck would have to become a scientologist to make this...er...wait a minute....

Other Sonic Obsessions - Hiphop Bebop Don't Stop

- Beastie Boys - Paul's Boutique

- A tribe Called Qwest - The Low End Theory

- A Tribe Called Quest - Peoples Instinctive Travels...

- KMD - Black Bastards

- De La Soul Is Dead

- Mad Villian - Mad Villainy

- Stereo MC's - DJ Kicks

- Miles Davis - Sorcerer

- John Coltrane - Live In Paris