I’ve always been a religious man, so I spent some good time praying that the “Post-National” world that Elliot Weinberger dreamed of in the summer 2005 issue of Tin House comes true. In those pages, Weinberger praised the growing prominence of the Post-National writer, the writer of exotic origin and tricky residence who was in the middle of revolutionizing western literature. But he also lamented that this revolution has so far been silent as the American audience had yet to embrace it.

As one of those writers he spoke of, I have found myself crippled by the choices that a supposedly less cosmopolitan reading world has left me with. After forty-five agents and fifteen publishers told me exactly the same thing, that my novel was too narrow, too dark, too foreign, not very accessible (but well written!) I was left with a dead manuscript that I destroyed and a writing career that was pretty much forgotten.

The fact is everybody blames the American reader for his narrow focus while envying his stacked wallet. And while there may be some truth to that, the far bigger problem is the industry that refuses to believe in the intelligence and open-mindedness of that very reader. The industry that will not take a chance on non-american, non-suburban white fiction unless it fits two very defined parameters, both of which I tried writing after my first novel was rejected.

The first is the immigrant novel. On paper it sounds foreign and exotic, but this is the most American of novels, for it details the quintessential American experience: Coming to America. The formula is pretty easy to trace. Ingredients: The stern patriarchal father who is beaten by a world that doesn’t want him; where he can’t be king, where his children no longer listen and where he is deplumed, de-wealthed and de-sexed. He grows withdrawn, bitter and sometimes malevolent. But let’s not forget the matriarch, the spiritual keeper of the cultural flame, the difficult one; the one in the family who never learns English and wants to get her daughter married as soon as possible. Coming through the front door at that very moment is the same aforementioned daughter, dressed like Britney and talking ghetto. Leaving through the back door is the son, having rebelled and felt the consequence, he drifts into that American no man’s land, making pit stops in gangs, drugs or troubled racial and/or sexual identity. In a very great sense the essential theme of these novels, the duel-duet of clashing cultures has been an American story ever since John Smith gave Pocohontas small pox.

It’s a cynical statement to be sure, but the cynicism is in response to the expectations of the publishing industry and not the novels themselves, some of which have been the most striking fiction of past 30 years. But in opening a tiny space, these novels shut out all other forms of post-national fiction save one: The white man trapped in the heart of darkness novel.

It’s a hell of a thing when you’re not white enough to write a black novel. On my 63rd rejection I hatched what seemed to be a clever idea. I would re-submit my novel to the same agents and publishers—only this time I would use my good Australian buddy’s photo and an invented bio about my life in the Caribbean bush, a sort of Serpent and Rainbow redux. Given that few editors had even read the manuscript I had little concern that the same reader would come across the novel twice.

A white man had just won the Booker prize for a novel about an Indian (Yann Martel for Life of Pi), and I would merely be joining one of English literature’s most enduring and at times offensive traditions, a malady that has afflicted nearly every cosmopolitan white writer not named Gordimer: The White man or woman who travels to the exotic land of darkness to find his inner light novel. The formula, hatched by Defoe, perfected by Conrad and being reinvented as I write this has long been the proven way to make foreign fiction work. Set the jaded white among the poor but proud natives and sooner or later he will learn something deep about him or herself, even if the natives never evolve from the noble or ignoble savages that they are.

Again, This is supposedly cosmopolitan fiction that is anything but, for it merely reinforces the essential differences (those pesky, backward natives) or cosmic similarities between people who try to co-exist and never moves beyond that point. As for the non-white characters, even the word character is a stretch as these men and women never evolve, never contradict, never waver, never grow, never change, in short, never become human.

And yet there is another kind of white penned, colored story, that goes even deeper than that; what Dale Peck calls the feat of Cultural Ventriloquism. In this novel the trick is to show just how deep in a foreign culture one can dig, the deeper the better. It’s the Jamaican novel that Russell Banks or Michael Tolkin can sell, but Patricia Powell cannot. It’s the Anansi story that becomes a gold mine for Neil Gaiman, but a black hole for Earl Lovelace. Unless one plays the rootless, quasi-mestizo, I’m both and neither angle that VS Naipaul plays. The fact is, the black story is far more sellable when it comes from a white voice.

Those were my choices as a writer, so I chose a third, to give up on writing altogether. No one wants to write a book that nobody will read, no matter how post-national you think you are. And yet not everybody wants to write something merely for its supposed commercial potential no matter how it easy it is to write it. There were so many people in this industry convinced that I had written a book that will never be read that I believed it myself, went back to writing commercials and burnt the manuscript.

But that was a black and white response to a black and white fallacy of a writing world that has always been gray. Or to put it in a less convulted way, I hadn’t figured on the fourth option: independent publishers. Through a series of accidents that one should never try at home, my manuscript found its way into an acclaimed writer’s hands who sent it to and agent who pretty much told me all I’ve heard before (I love it! Nobody else will!) and an independent publisher, Akashic Books who fell for the manuscript and has since published it. But even in that situation I sometimes came upon two opposing halves of the same prejudice. While one side rejected the post national author and one side embraced, both were convinced of the writer’s limited potential (with the notable exception of the guy who published my book). Maybe both are right.

The problem with this insistence on formula is that the American reader has already proven it untrue. Formula cannot explain the success of Khaled Rossini’s Kite Runner or the failure of George Hagen’s The laments. It obscures Orham Pamuk’s success with My Name is Red.

What does that leave for us, post nationals, for whom no amount of bitterness can obscure one true fact: that we want to break into America? Write for the people you know and hope everybody else catches on? I really don’t know. I know I’m selling books one at a time, in independent bookstores and cafés all over the US, trying to prove that a story set in a Jamaican village is not that much different from one set in a small, American town, and even if it is, that we still love heroes, hate villains and want good to triumph over evil. It’s both rewarding and frustrating and I do question why am I doing this every day.

But as I write my second book the same demons have come back to haunt me. Acclaim is nice, such as it is, but how about some sales? How local can I be? Should I move my characters to Brooklyn? If I move to a larger publisher (assuming they would want me) will the New York Times review my book? How much Jamaican dialect is too much? Do I have the requisite 4.25 white characters? And what language should they speak? How will all of this sell? Will William Morris give me a call?

These are all terrible things to take to a writing desk, so in the end I think of nothing but the story. I have to hold to the belief that book and reader have an almost cosmic destiny to meet. And when they do, no barrier whether it be language, race, culture or nationality will stand in the way. In other words, Elliot, I’m placing all my bets on the hope that there are more people in the world just like you.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

CHEEVER, A LIFE, by Blake Bailey: Engrossing, maddening, funny but also unbearably sad, Cheever's greatest work of fiction may have been himself

In Hazard, by Richard Hughes

-image007.jpg)

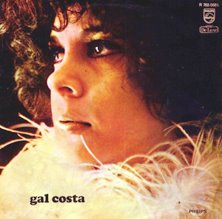

GAL COSTA. You get the feeling that the tropicalia subversives were really trying to make a hit with this one, and it's all the better for it. Beck would have to become a scientologist to make this...er...wait a minute....

As Of The Writing I, Marlon James

- Marlon James

- Minneapolis/ St. Paul, United States

John Crow's Devil Paperback UK

John Crow's Devil Paperback USA

READING RIGHT NOW...

CHEEVER, A LIFE, by Blake Bailey: Engrossing, maddening, funny but also unbearably sad, Cheever's greatest work of fiction may have been himself

Reading Right Now...

In Hazard, by Richard Hughes

Books Of the Moment

- American Rust, by Phillip Meyer

- The Liar's Club, by Mary Karr

- The Forever War, by Dexter Filkins

- Sacred Violence, by Paul W. Kahn

- The Pilgrim Hawk, by Glenway Wescott

Rocking My World

-image007.jpg)

GAL COSTA. You get the feeling that the tropicalia subversives were really trying to make a hit with this one, and it's all the better for it. Beck would have to become a scientologist to make this...er...wait a minute....

Other Sonic Obsessions - Hiphop Bebop Don't Stop

- Beastie Boys - Paul's Boutique

- A tribe Called Qwest - The Low End Theory

- A Tribe Called Quest - Peoples Instinctive Travels...

- KMD - Black Bastards

- De La Soul Is Dead

- Mad Villian - Mad Villainy

- Stereo MC's - DJ Kicks

- Miles Davis - Sorcerer

- John Coltrane - Live In Paris